Supports identified by experts

“There are so many barriers to participate in real mobility for young people with disabilities. In my opinion, we should first remove these barriers before talking about virtual mobility as a miracle solution to get more young people with disabilities involved.”

Fabrice Beaumont, Head of the Mobility Department, Romans International, Romans-sur-Isère:

In the Virtual Mobilities 4 All-project, the virtual mobility of vulnerable young adults is addressed. Particularly young adults with disabilities should be encouraged to use virtual mobility. Given the very broad heterogeneity of this group, the supports identified by experts varies very much.

In our project we have interviewed 33 experts from different fields like social work, public health, education and inclusion and so on. In this short overview, we will present only some examples of supports identified by experts in order to give a glimpse of the practice of the use of virtual mobility for young adults with disabilities. If you are interested in taking a deep dive into the reports that were based on these interviews, you can find it the full report here and a summary here.

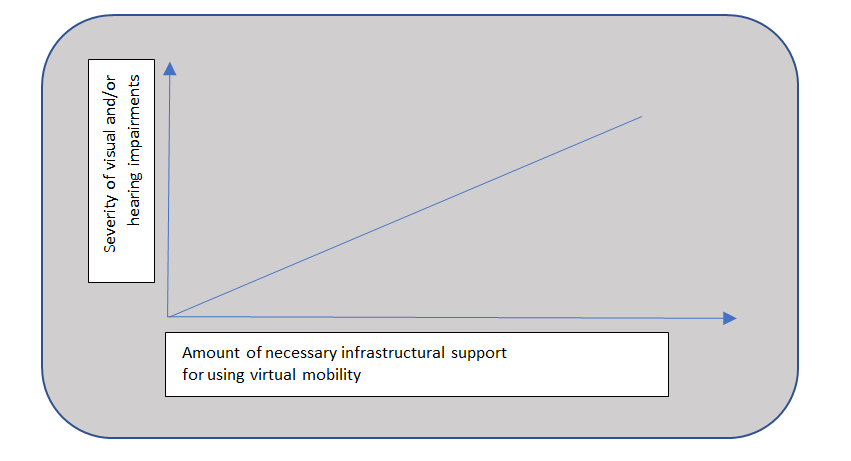

Heterogeneity of demands of support by different groups of disabled people

The organisations that support people with disabilities are highly differentiated, following the very heterogeneous demands of people with disabilities in general and young adults with disabilities in particular. The amount of necessary infrastructure depends directly on the severity of impairments.

Results from expert interviews and organisational analysis

In our interviews with experts from various organisations it was said in all six different countries, that often the resources and technical infrastructures that could be offered to the young adults with disabilities are not adequate to meet the needs of this vulnerable group. In the interviews, people from different fields and countries complained about the lack of accessibility of web pages for people with disabilities and claim for a barriers-free internet. The diverse range of support organisations provide vital services for many people with disabilities and try to create raising awareness for the digital needs of people with disabilities.

However, the very diversity and the local nature of many of these organisations results in both a lack of coordination at city or regional level and something of a lottery as to what services may be available in any particular location or for any particular disability.

With regard to virtual mobility there is very often a lack of experience, knowledge and infrastructure to give young adults with disabilities the opportunity to use virtual mobility. This is true even for statutory and non-statutory organisations with decades of experiences in orthodox social work.

In Germany for instance a person mentioned that she had almost no knowledge and hardly any interest in virtual mobility even though she organized large digital conferences on inclusive education. The same is true for many other organisations across Europe where virtual mobility plays a limited role with its members and young people.

But there are nevertheless many examples of good practice that combine support of people with disabilities with digitalized formats, virtual reality, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) and so on. Examples are for instance AsIAm – Ireland’s National Autism Charity, the IVRAP project, coordinated by The University of Valencia, aims to teach students on the autism spectrum and learning difficulties how to ‘learn to learn’ by developing and assessing an Immersive Virtual Reality (IVR) educational tool.

Furthermore, the University of Vigo that is the only Spanish educational institution that participated in a European project that seeks to promote inclusion in international mobility programmes. The initiative, called Social Inclusion and Engagement with Mobility (SIEM), aimed to increase the presence of students from disadvantaged or underrepresented groups in the Erasmus+ programme, in which they account for 7% of participants (instead of an average rate of 0.7%).

Even though students with disabilities are facing problems after getting support, the University of Pau (France) offers a variety of offers for different disabilities to support long-distance students. Additionally, the organisation “Open the windows” from Northern Macedonia is fully committed to promoting assistive technology, providing access for people with disabilities to computers and the internet. Introduces assistive technology in regular education. Finally, the NGO “Me Alla Matia” (“With different eyes”; Greece) founded in 2018 is providing information for people with disabilities, their families or professionals. Me Alla Matia tries to provide job opportunities for disabled people through projects’ implementation. For now, they mostly work in consulting accessibility and in digital environment and they are in the middle of a project, the aim of which is to familiarize students in schools with disability issues by bringing them in contact with people with disabilities.

Conclusion

Apart from these general individual skills and personal characteristics that can assist individuals to participate in virtual mobility opportunities, it tends to be particular structural resources that emerge as a necessary precondition or at least extremely important in facilitating access.

With respect to the compiled list of different virtual mobility activities, it is clear that students across mainstream school, vocational and university settings require organisations that can access systematically established virtual mobility-projects.

Along the lines of students, workers need to be supported by their enterprises or organisations to be able to participate in virtual mobility if skills and competencies should be developed that will be best applicable to the learning setting or to the working environment.

It is important to note that relevant stakeholders in organisations have to be well informed about mobility and virtual mobility programmes like Erasmus+ to support members and staff. Here, it becomes clear that young adults who are not linked to any learning institution or enterprise because of early school leaving and/or unemployment and/or sickness the participation for those individuals is systematically impeded and very often left either to the individual commitment or to significant others like parents.